National media: Keogh says 13k NHS deaths! Keogh: er, no I don’t.

Access to General Practice and Emergency Department attendance in UK. A link to poverty?

16 Jun

The paper from Imperial College evaluating Emergency Department use with reference to access to a General Practitioner during the year 1 April 2011- 31 March 2012 here in England caused a small storm when it was published last week (June 13, 2013). At face value, the results play into the Government’s narrative that GPs are lazy, do not see enough patients, and Emergency Departments are overwhelmed by honest citizens who were not able to see there GP at the time of their choosing (Cowling et al, 2013). The perception was propagated elsewhere, including the fledgling The Conversation UK .

Here are some reasons why the conclusions are flawed in my opinion.

-

The General Practice Access Questionnaire surveying the percentage of people who stated that there was poor 48 hour access to see their general practitioner is widely discredited by general practices as bearing no relationship to the reality of access to their practices

- Too few non-British respondents compared with true practice profiles (84.9% white) and relatively too many men (49.8%) compared to usual pattern of GP utilisation

- Many respondents actually have no idea how their own practice operates, this particularly true of male patients who use GP infrequently.

- No stratification for illness episodes people felt required 48 hour (or less) access to GP

- No effort to look at patient outcomes from failure to see GP within 48 hours.

- < 4% practice population completed the forms which is arguably too low to be meaningful (2 million respondents of population of 56 million)

-

Hospital Episode Statistics ED minimum dataset too simplistic

- No detailed disease code for reason for attendance

- No outcome data as a result of (a)

- Indicator variables for the Strategic Health Authority in which a general practice is located were included to account for unobserved variation in regional health system characteristics and policy. This is too crude to assess pockets of deprivation which every practice has, and some more than others.

Cowling et al observed that

The median percentage of a practice’s registered population that had tried to see a GP within two weekdays in the past six months was 59.3% (IQR: 54.9–63.6%). This demand was not always met: the median percentage that was subsequently able to do so was 82.0% (IQR: 74.0–89.3%).

You must keep in mind that this number refers to the GPAQ results, not actual numbers. The GPs I know do not recognise the result as properly describing the access to their practices.

In their discussion

In 2011-12, 9% of respondents to the GP Patient Survey who were unable to obtain a convenient appointment on their last attempt report subsequently going to an ED or walk-in centre, which accords with the results of our analysis.

Which simply validates their dataset rather than really telling us any more about the reasons for the behaviour.

And Cowling et al are dismissive of data which does not support their thesis suggesting to me that their minds were made up before this statistical paper was completed and the data have been made to fit the narrative.

Previous research of 68 general practices in London, England did not identify a statistically significant association between patient-reported access to general practice services and the rate of self-referred discharged ED visits, possibly due to insufficient statistical power. This explanation may also apply to a similar analysis of 145 practices in Leicestershire, England, which included all types of ED visit in the outcome variable.

Referring to North America data on GP access is not helpful because there is not universal coverage for primary health care like here in UK. In fact, it can be argued that the data confirms poverty and low social class as determinants of unplanned hospital (e.g. Emergency Department) use.

Looking at some common conditions which may influence ED

the prevalence of obesity in the registered population had a statistically significant positive association with the rate of ED visits (RR = 1.006; P = 0.021), whereas the prevalence of asthma and hypertension did not

indicates to me that the population who filled in the GPAQ do not properly represent disease prevalence or people who attend the practice regularly do know how to access their GP promptly and do so successfully. This mocks the conclusions of the study.

The results of this study do not support the hypothesis that timely access to GP could reduce self-referrals to the Emergency Department. What the study tells us is that some white English people cannot be bothered to wait to see their GP for self-limiting conditions. There is some evidence supporting the view that self-referral to Emergency Department is associated with low social class, poor education, and poverty. This is inferred from the observation that obesity has a positive association with ED attendance; obesity is closely linked to unfavourable social factors http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2013/jan/23/fact-checking-obesity-poverty-link This is exacerbated in the current economic climate and further worsened by a Government pushing much and more onto General Practices since 2004 a lot of which is clinically useless. For example, Health Checks, GP access initiatives, ambulatory blood pressure recording to diagnose hypertension, routine reviews of people with long term conditions who are stable.

I believe part of the problem of perceived poor access to see a GP has been created by the UK Government fanning flames of expectation by the worried well. Practices must make more routine appointments available for people with long term conditions, must not turn away anyone who wishes to be seen in hours, and can no longer depend on expert community nursing to help out. Finally, the hardships many of my patients face in their living conditions because of unscrupulous landlords and local authorities turning blind eye to the tenants’ grievances is exacerbating the problem.

The paper by Cowling et al does support the Government’s assertion that General Practice and GPs are not working hard enough. It is clear to me that the research is flawed and the main conclusion is unfounded.

June 2013

{EAV:374807f8ed8c63d9}

Underactive thyroid disease – a modern approach

9 Jun

The Problem

A patient comes to the doctor concerned about longstanding fatigue symptoms. She knows of a family history of underactive thyroid disease and is worried her thyroid is not working properly

Introduction and some basic concepts

[from Basic endocrinology : for students of pharmacy and allied health sciences, edited by Constanti et al (1998; ISBN 9780203301739) ]

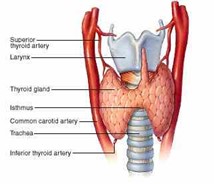

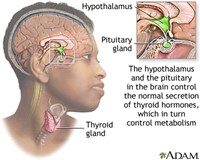

The thyroid gland lies in front of the trachea below the larynx. The hypothalamus and pituitary control normal secretion of thyroid hormones. The thyroid hormones in turn control the body’s metabolism. The two active hormones are iodinated derivatives of the amino acid tyrosine. Nearly 90% of the output is thyroxine (T4) containing four iodine atoms while nearly 10% of the output is triiodothyronine (T3) containing three iodine atoms. In health < 1% “reverse” T3 (rT3) is released; this increases in presence of severe illness or starvation. In the bloodstream the thyroid hormones are extensively bound to plasma proteins, principally thyroxine binding globulin (TBG).

Note that in patients on T4 replacement all T3 is produced by peripheral conversion, and so circulating T4 levels may need to be maintained slightly above the “normal” reference range to generate adequate tissue T3 concentrations.

So far so good that is what medical students and other healthcare professionals have been taught to decades. The thyroid stimulating hormone from the pituitary goes up when/if thyroid hormone levels too low, and vice versa.

However this is not the whole story. A more detailed appreciation of the nuances of thyroid hormone metabolism are required to appreciate why so many people with underactive thyroid disease continue to struggle to regain normal health. For example, the story of Coralie Phillips and Donna Roach gives pause for thought about one of the most neglected conditions in general medicine http://www.thyroidbooks.co.uk/ .

Underactive thyroid disease (UAT) is considered simple to diagnose and simple to treat. Luckily this is the case most of the time. Unfortunately when the approach does not seem to be working effectively patients are labelled as difficult or dismissed as mentally ill instead. The medical establishment generally has failed to treat people with UAT scientifically by looking at factors which may conspire to prevent the neat outcome which is expected.

The purpose of this brief essay is to highlight these pitfalls in the hope that fewer people with UAT will suffer in future.

Modern thyroid hormone biochemistry

Role of vitamin D

It seems that adequate levels of vitamin D are necessary to maintain thyroid health.

For example (http://www.endocrine-abstracts.org/ea/0032/ea0032p1008.htm): In this study of 100 patients with autoimmune hypothyroidism compared to 100 subjects as control group, the higher vitamin D deficiency rates besides lower vitamin D levels in the Hashimoto group together with the inverse correlation between vitamin D and anti-TPO suggest that vitamin D deficiency may have a role in the autoimmune process in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Conversely, some evidence emerging that high levels of T3 may suppress vitamin D levels (e.g. http://endo.endojournals.org/content/154/2/609.short) This may be one mechanism for bone losing state of untreated hyperthyroidism (or over-treatment of UAT)

Role of vitamin B12

A new abstract summarises the impact of low vitamin B12 on thyroid disease (and other [geriatric] conditions http://www.bioline.org.br/abstract?rc13008):

Vitamin B12 deficiency is a common condition in the elderly. It is repeatedly overlooked due to multiple clinical manifestations that can affect the blood, neurological, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular systems, skin and mucous membranes. The various presentations of vitamin B12 deficiency are related to the development of geriatric syndromes like frailty, falls, cognitive impairment, and geriatric nutritional syndromes like protein-energy malnutrition and failure to thrive, in addition to enhancing aging anorexia and cachexia. Therefore, interventions must be developed to include their screening and diagnosis to make early and appropriate treatment to prevent its complications before they become irreversible.

Role of trace minerals

A detailed overview of heavy metals by a nanotechnology team illustrates how important optimising the levels can be for cellular health and ascorbic acid/Krebs cycle [http://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-0413/ijsrp-p16110.pdf]

Iron (Fe) Contained in hemoglobin and myoglobin which are required for oxygen transport in the body. Part of the cytochrome p450 family of enzymes. Anemia is the primary consequence of iron deficiency. Excess iron levels can enlarge the liver, may provoke diabetes and cardiac falurer. The genetic disease hemochromatosis results from excess iron absorption. Similar symptoms can be produced through excessive transfusions required for the treatment of other diseases.

Copper (Cu) Contained in enzymes of the ferroxidase (ceruloplasmin?) system which regulates iron transport and facilitates release from storage. A structural element in the enzymes tyrosinase, cytochrome c oxidase, ascorbic acid oxidase, amine oxidases, and the antioxidant enzyme copper zinc superoxide dismutase. A copper deficiency can result in anemia from reduced ferroxidase function. Excess copper levels cause liver malfunction and are associated with genetic disorder Wilson’s Disease

Manganese (Mn) Major component of the mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme manganese superoxide dismutase. A manganese deficiency can lead to improper bone formation and reproductive disorders. An excess of manganese can lead to poor iron absorption.

Iodine (I) Required for production of thyroxine which plays an important role in metabolic rate. Deficient or excessive iodine intake can cause goiter (an enlarged thyroid gland).

Zinc (Zn) Important for reproductive function due to its use in FSH (follicle stimulating hormone) and LH (leutinizing hormone). Required for DNA binding of zinc finger proteins which regulate a variety of activities. A component of the enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase, lactic dehydrogenase carbonic anhydrase, ribonuclease, DNA Polymerase and the antioxidant copper zinc superoxide dismutase. An excess of zinc may cause anemia or reduced bone formation.

Selenium (Se) Contained in the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase and heme oxidase. Deficiency results in oxidative membrane damage with different effects in different species. Human deficiency causes cardiomyopathy (heart damage) and is known as Keshan’s disease.

Fluorine (Fl) Constituent of bones and teeth. Important for tooth development and prevention of dental caries. Derives from water, tea, and fish.

Cobolt (Co) Contained in vitamin B12. An excess may cause cardiac failure.

Molybdenum (Mo) Contained in the enzyme xanthine oxidase. Required for the excretion of nitrogen in uric acid in birds. An excess can cause diarrhea and growth reduction.

Chromium (Cr) A cofactor in the regulation of sugar levels. Chromium deficiency may cause hyperglycemia (elevated blood sugar) and glucosuria (glucose in the urine).

A recent Turkish paper indicates low zinc levels in saliva (and so plasma) in people with UAT [http://www.turkjem.org/sayilar/79/buyuk/1-4.pdf]. It is not known if this is a cause or effect of UAT but suggests that people with UAT should ensure zinc levels are optimised.

Role of reverse T3?

A recent study highlights the dangers of subclinical hyperthyroidism considering healthy aging associated with decline in T3, unchanged levels of T4, with rise in TSH and rT3 [http://goo.gl/WCUk8]

The process of normal aging affects the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in a number of ways, resetting of the set point being the most important of them. Contrary to the earlier belief, longevity has been reported to be associated with high serum TSH. Most recent studies have demonstrated an age dependent decline in serum free T3 levels, whereas FT4 levels remains relatively unchanged and TSH & rT3 levels increase with age. Two recent meta-analyses have shown increased risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients younger than 65 years of age, but not in those more than 65 year old. There is a good number of evidence documenting increased mortality in elderly individual with sub- clinical hyperthyroidism, which should be kept in mind while treating mildly elevated TSH in these patients. It is also important to remember that thyroid functions in the elderly closely mimics that found in sick euthyroid syndrome.

People with UAT recognise that rT3 levels can rise while they are ill. They make a good argument that rT3 levels ought to be checked in cases of poor response to standard treatment. If rT3 is raised then clearly the the patient is ill and efforts need to be made to restore her/him to biochemical euthyroid state.

Thyroid stimulating hormone response is not predictable

A recent paper by JEM Midgley highlights the problem with depending on TSH to determine whether or not a person with thyroid disease is adequately treated [http://jcp.bmj.com/content/66/4/335.abstract and http://www.hindawi.com/journals/jtr/2012/438037/]

Our data suggest that the states of hypothyroidism, euthyroidism and hyperthyroidism can be regarded as differently regulated entities. The apparent complexity could be replicated by mathematical modelling suggesting a hierarchical type of feedback regulation involving patterns of operative mechanisms unique to each condition. For clinical purposes and assay evaluation, neither the standard model relating logTSH with FT4, nor an alternative model based on non-competitive inhibition can be reliably represented by a single correlation comparing all samples for both hormones in one all-inclusive group.

Conclusion and approach to the patient

UAT is a common condition though there is still a lot to learn how to accurately diagnose it in all patients. Even if the diagnosis is not elusive the patient’s response to treatment is occasionally not what is expected.

To ensure improved diagnostic accuracy free T3 ought to be checked for all patient suspected of suffering UAT.

Thus it is my practice to check the following in a person who presents with a longstanding history of fatigue with no obvious abnormality on physical examination:

- Full blood count with vitamin B12, folic acid and transferrin saturation index for iron status

- Thyroid function test, including free T3 as well as free T4 and TSH

- C-reactive protein

- Vitamin D level and calcium profile

If patient is proved to have UAT, treatment is started at 25 mcg daily of thyroxine. The patient will be reviewed approximately 2 months later when thyroid function is rechecked with fT3, as well as checking thyroid peroxidase autoantibody (for autoimmune thyroid disease). If there has been a poor response to treatment, copper, zinc and 9am cortisol level should also be checked. rT3 should be checked in all poor responders to treatment too; this is recommended by Thyroid UK.

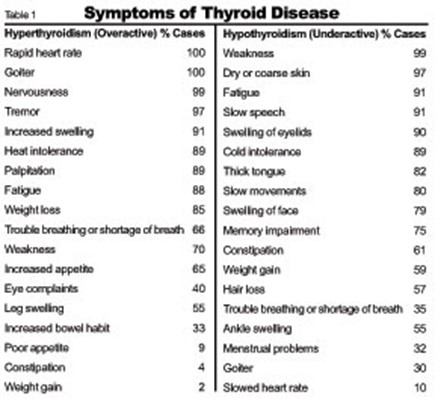

For details about signs and symptoms of UAT see for example: patient.co.uk

http://www.hormone.org/diseases-and-conditions/thyroid

Some patient resources

UK

Thyroid UK – http://thyroiduk.healthunlocked.com/ http://www.thyroiduk.org.uk/tuk/index.html

International

American Thyroid Association – http://www.thyroid.org/

Association Française des Malades de la Thyroïde – http://www.asso-malades-thyroide.org/

Petition – Better Endocrinological Service and Treatment for Thyroid Patients in United Kingdom

If you agree that more should be done for people with thyroid disease, then please sign the petition here

David Lewis

Hertfordshire

June 2013

Beginners Social Media in Medical Education

7 JunKaren has captured the mood about using social media as (medical) professional education tool. Well worth reading!

So we need to talk about Social Media.

I helped to present at the Women In General practice conference a Social Media familiarisation session for Female doctors. This was held on June 1st 2013 at Yarra Valley Lodge about an hour north of Melbourne Victoria, Australia. This by the way is my first blog too so the adventure into the online medical space continues.

My talk segment was about Medical Education via Twitter.

I puzzled over how to introduce SoMe Med Ed to the non-convinced.

Medical Education on Twitter

I discussed 140 characters with links to be saved or short articles as an ideal way for time poor female GP’s to broaden their range of access to medical journal articles and international medical opinion.

I demonstrated the great medical organisations on Twitter; I demonstrated the fabulous Medical Drs both international and local that I follow; I demonstrated all…

View original post 1,207 more words

Quality of care is ‘not a priority’ in NHS – PharmaTimes

26 MaySee on Scoop.it – Of human kindness

Quality of care is ‘not a priority’ in NHS PharmaTimes Quality of care is ‘not a priority’ in NHS. New survey of NHS professionals finds a vast majority do not believe that quality of care in the health service is given enough priority.

Quality of care is priority for all healthcare professionals who have direct contact with patients; anyone who doesn’t should be removed from frontline services in my opinion. However, health service managers may subscribe to Welfare Utilitarianism philosophy which places quantity over quality; a philosophy which must be challenged if (UK) citizens want assurance of quality care when required. See http://www.humanvaluesibhealthcare.com to understand why?

See on www.pharmatimes.com

Rise Of The Patient #ROTPt: A Trilogy in Health Care

12 AprSee on Scoop.it – Of human kindness

Join me, Shirley Williams, as I interview Dr. David Lewis as he shares his life experience in the health care system as a Family Doctor, Patient and Caregiver. Bio David Lewis FRCSEd, MRCGP David Lewis is a family doctor in United Kingdom.

If you have a moment, why not listen to my interview with Shirley.

See on www.blogtalkradio.com

Rubbish in, rubbish out – clinical coding pitfalls undermine travails of NHS

17 MarBrilliant essay illustrating importance of clinical coding in managed healthcare system

In the immediate aftermath of the release of the Francis Report into events at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, I identified that David Cameron’s crocodile-tears and apparent humility were just a feint that would quickly turn into an attack on the NHS nationally (yet another front in their all-out war on it), using Mid Staffs as a template for attacking other hospitals – and Labour.

This morning’s headlines – covered by the BBC (website and news channel) and the right-wing press – about Professor Sir Brian Jarman’s claim that 20,000 NHS deaths could have been prevented come on the back of a 2-week long assault by Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt on Labour’s supposed failings leading to Mid Staffs.

The claims are utter nonsense – but they are being used by the press and the government as

A sledgehammer to smash the NHS – and Labour

I’ve already shown, at…

View original post 3,323 more words

Revised Section 75 regs mire CCGs in a legal minefield

12 MarFurther trouble not less after Government tables revised regulations on competition for providers. Who would be a Commissioner?

Vitamin B12 deficiency – time for a rethink?

2 MarTraditional view

NHS Choices offers a traditional view of vitamin B12 metabolism and diagnosis and management of vitamin B12 deficiency anaemia.

An up to date review was published recently link

Vitamin B12 deficiency anaemia or folate deficiency anaemia develops when a lack of vitamin B12 or folate causes the body to produce abnormally large red blood cells that cannot function properly.

The main symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency or folate deficiency anaemia are:

- tiredness

- lethargy (lack of energy)

View from special interest group(s)

Conversations with members from Pernicious Anaemia Society and B12 deficiency support group indicate there is more to the cobalamin metabolism story than the traditional view describes.

Recent articles and abstracts scattered through the scientific literature point to a more sinister effect on human biology when there is functional deficiency of B12.

- Functional vitamin B12 deficiency may occur at any serum level of vitamin B12 [link]

- Vitamin B12 Deficiency Associated With Concomitant Metformin and Proton Pump Inhibitor Use [doi: 10.2337/dc12-0980Diabetes Care December 2012vol. 35 no. 12 e84]

- Metabolic Globus Pallidus Stroke in Transcobalamin II Deficiency. [JIMD Rep. 2013 Feb 21]

- Adenosylcobalamin essential cofactor for part of the Krebs Cycle, the key energy generator for cellular respiration by mitochondria. Details recently summarised by Hugo Minney at B12D

Adenosylcobalamine, the adenosyl form of Vitamin B12, is needed to keep the TCA cycle running smoothly, and many people with B12 deficiency suffer a “dreadful fatigue”. But it’s a complicated process getting B12 into mitochondria, and an awful lot of things can go wrong.

A key to better understanding is awareness of biochemical reactions in which vitamin B12 is a crucial. These include [link]:

- conversion of odd chain fatty acids (specifically propionate) into succinate

- conversion of homocysteine into methionine via methyl group donation

Medically Unexplained Symptoms – is this a B12 deficiency syndrome?

This week it was proposed that any patient with medically unexplained symptoms should be referred for CBT. It was estimated this may save the NHS £3 million per year. No mention by the authors of the report to explicitly exclude functional deficiency of vitamin B12 [Advances in Psychiatric Treatment (2009)15: 146-151doi:10.1192/apt.bp.107.004606]

Do not forget magnesium deficiency – it is important to ensure magnesium levels are normal in any patient who is taking high dose proton pump inhibitor especially if also prescribed a diuretic agent.

The neuropsychiatric changes caused by functional B12 deficiency may predate the typical changes seen in the blood by months (perhaps years). These are detailed by MacDonald Holmes [JMD Holmes – British Medical Journal, 1956].

McAlpine (1929) said, ” Mental changes occur not uncommonly in pernicious anaemia. They range from states of depression accompanied by loss of mental energy to definite psychoses…” [McAlpine, D. (1929). Lancet, 2. 643]

When there is doubt about the status of vitamin B12 rather than repeat the test in 6 weeks in “borderline cases” as is the present practice, serum methylmalonic acid levels and serum homocysteine levels should be measured.

Measurement of methylmalonic acid, total homocysteine, or both is useful in making the diagnosis of vitamin B12 deficiency in patients who have not received treatment. The levels of both methylmalonic acid and total homocysteine are markedly elevated in the vast majority (>98%) of patients with clinical B12 deficiency including those who have only neurologic manifestations of deficiency (i.e., no anemia). [Stabler, S NEJM 2013]

Implications for general practice

Clearly there is a need to review how we view vitamin B12 metabolism. Recognition in primary care of functional deficiency of vitamin B12 will require medical curricula to pay better attention to this. Haematology does not have a monopoly on clinical features of vitamin B12. There are too few haematologists and neurologists, at least in the UK to provide clinical opinions when vitamin B12 deficiency is suspected. This leaves it to general practice and family doctors to learn more about the protean manifestations of altered vitamin B12 metabolism.

With performance managed healthcare becoming the norm around the world, it may be time to press for explicit scrutiny of vitamin B12 levels in patients with long term conditions including many in the following systems: gastrointestinal, hepatic, psychiatric, neurological, endocrine, renal, and non-malignant anaemias. Only then might we be certain that a scourge of (modern) society will be beaten.

David Lewis

GP UK

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank @b12unme for educating me about this issue. Any errors and omissions are mine.

Netiquette – playing nice on social media

24 FebA short note here following the helpful twitter chat today with #hcsmanz [transcript link]

Background

Wikipedia defines netiquette. However, the clearest summary is contained in the following picture:

Better understanding of the conventions for engaging in social media conversations will, hopefully, get more people to stop lurking and join in. Social media conversations are more than tea time conversations. Social media is not only “social” but can be a powerful tool for professional development.

Resources or not reinventing the wheel

Link at Learn the Net – Your online guide

BBC Webwise making the most of being online.

A useful podcast for social media education is The Social Hour [Friday’s 2100 UMT]

Some examples – why social media matters for health and social care

Link to Youth Health 2.0

for articles on social media and mobile technology in public health, e.g.

- Social media and the medical needs of American Indians

- The art of engaging indigenous youth via social media

For (health and social care) professionals @brookmanknight has the last word:

“with medical people I talk collaborative peer support open access learning. Social as a word is not useful to engage or invite.”